Jewish Fürstenwalde

The earliest documents mentioning Jewish inhabitants in the areas east of the Elbe date back to the 13th century and thus fall into the late phase of High Medieval land settlement and Ascanian rule in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. Conceivable, yet unproven, is the immigration of Jews as early as 1096 from the Rhineland in the wake of the religious persecutions connected to the First Crusade. The first recorded mention of a Jew in Fürstenwalde dates from 1379 and concerns an individual called David, who was sentenced to death by burning.

Jewish life in the towns of the Margraviate was determined by the regional ruler’s laws and the so-called “Judenordnungen” (Jews’ ordinances), and was consequently dependent upon the interests of the king, the prince-elector, the town council and the guilds. In urban communities dominated by Christians, Jews often faced rejection, exclusion and even persecution and violence.

In 1571, all Jewish residents were expelled from the Margraviate of Brandenburg. It was not until the second half of the 17th century that the regional rulers permitted Jewish families to settle there once again, issuing writs of protection for them. Jews did not return to Fürstenwalde until around the mid-18th century. The town council hoped in this way to revive the town’s poor economic situation and placed the four newly-settled families under protection. The oldest gravestone from the old Jewish cemetery, located at the “New Gate” outside the town wall, dates from 1746. The new cemetery in Frankfurter Straße corner of Grünstraße was established in 1829.

The jewish community of Fürstenwalde

In the first half of the 19th century, around 50 Jews were living in the town. Initially, they belonged to the Jewish congregation of Frankfurt (Oder), but by 1879 they had established their own autonomous congregation. At that time, around 100 people of Jewish faith were living in Fürstenwalde. Religious life was concentrated around the synagogue in Frankfurter Straße. The merchant Julius Meseritzer had converted a residential property for this purpose in 1870. The congregation employed a cantor, who also acted as shochet (kosher butcher), but it did not have its own rabbi.

In 1873, the Jewish pedagogue Markus Reich founded an educational institution for hearing-impaired Jewish children, the “Israelitische Taubstummenanstalt” (ITA – Israelite School for Deaf Mutes), at Neuendorfer Straße 5 in Fürstenwalde. It was the only institution of its kind in the entire German Empire. Indeed, the latter did not introduce compulsory education for all deaf-mute and blind children until 1911. The institution, which was funded by an association, enabled these children and young people to receive a basic education, but also offered vocational training and instruction in starting businesses. Training places were in such high demand that in 1888 the ITA had to move to a larger building on a more spacious site in the Weißensee district of Berlin.

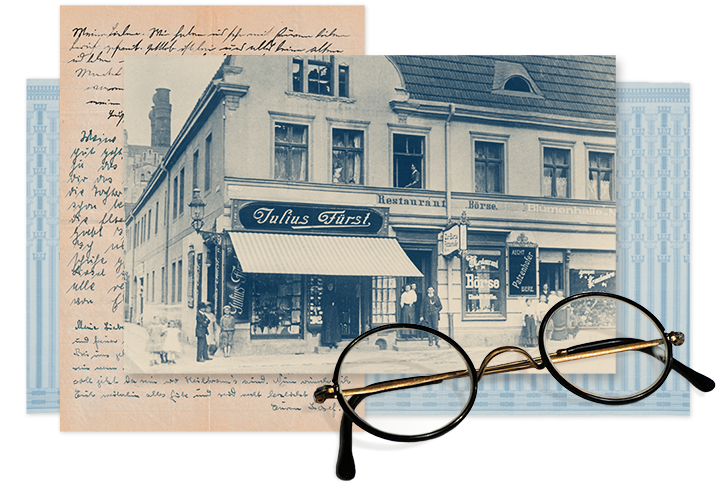

By the beginning of the 20th century, around 150 to 160 Jewish citizens lived all over Fürstenwalde. They worked as doctors, dentists, lawyers, photographers; they sat on the town council – like the long-time chairman of the Jewish community Hermann Casper – and ran businesses and department stores. On and around the town square, people could shop in the department stores of the families Marcuse, Fürst, Brandt, Gottfeld or Flatauer – with the latter boasting the town’s first lift. The shopping streets of Fürstenwalde contained a further 32 Jewish-owned shops.

The Henry Hall machine factory and iron foundry on the bank of the River Spree belonged to the Jewish Behrendt family. It is highly likely that the industrial plant “Gebrüder Pintsch Werke” employed Jewish workers. The chemist and inventor Dr Hans Klopstock worked in the Ketschendorf branch of “Deutsche Kabelwerke AG” (German Cable Works, today Fürstenwalde South), which had been founded by the Berlin-based Jewish entrepreneurial family Hirschmann.

In 1928, the Jewish community expanded its cemetery and solemnly inaugurated the mourning hall in a ceremony open to the broader public. There are unconfirmed rumours of a mikvah – a ritual bath – on Frankfurter Straße. In addition to serving the town’s Jewish community, the Fürstenwalde synagogue also served eight other Jewish communities in Alt-Madlitz, Beeskow, Berkenbrück, Briesen, Demnitz, Hangelsberg, Neuendorf im Sande and Bad Saarow.

In Neuendorf im Sande, an agricultural and crafts training camp, established in 1932, prepared Jewish adolescents and young adults for emigration, mainly to Palestine. About 200 young people lived in the Hachshara camp until 1941.

Hate and extermination

After the National Socialists seized power in 1933, the situation changed dramatically as Jews found themselves facing increasing levels of hatred and humiliation. Many families left the town. During the pogroms that took place on and around 9 November 1938, the fascists wantonly smashed and looted most of the shops, set fire to the synagogue, and desecrated and destroyed the cemetery and its mourning hall. Numerous male Jews were sent into “protective custody”, mostly to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939, no more than 26 Jews were still living in Fürstenwalde. In 1941, those of the town’s remaining Jewish inhabitants who were not protected by being in a so-called “mixed marriage” were deported to their deaths.

In 1941, the National Socialists converted the former Jewish training camp in Neuendorf im Sande into a forced-labour camp, where they imprisoned young people from various German Hachshara camps. The best-known forced workers of Neuendorf were the musician Esther Bejarano and the quizmaster Hans Rosenthal, who had to work in a flower shop or at the cemetery in Fürstenwalde. By 1943, all prisoners had been deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where most were murdered.

Text: Justyna Gralak

Translation: Jennifer Feldman