Reasons for Persecution

The persecution, imprisonment and extermination of people under National Socialist rule in Germany took place in a systematic and radical manner. Anyone who did not fit into the narrow and racist National Socialist way of thinking or did not conform to the Nazis’ ideological and societal conceptions was a potential victim.

By far the largest persecuted group was composed of Jews. It is estimated that throughout Europe the National Socialists murdered more than six million people they defined as Jews in the pursuit of their “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”. The National Socialist terror was also directed ruthlessly against Sinti and Roma, Afro-Germans and political dissidents – including communists, socialists and critics of the system. From a position of deeply rooted anti-Slavism connected to its race-based ideological reasoning, Nazi Germany also prosecuted its war of extermination against the population of Eastern Europe as a whole.

People with disabilities, the “hereditarily defective”, homosexuals and “antisocial elements” fell victim to the system, as did Jehovah’s Witnesses. In most cases, their persecution did not encounter any open opposition, but was met rather with the silent consent of society and the elites.

National Socialist racial ideology divided groups of people into “races” and ascribed to them a characteristic hereditary disposition that was biologically based and considered to express itself in typically negative forms of behaviour and ways of life. In this context, Jews were defined as the most important hostile “race” and, at the same time, as a threat to the self-proclaimed “Aryan master race”.

Actual membership of the Jewish religious community played no role in these considerations. The sole and decisive factor was a person’s family origins. Therefore, converts to Christianity or secular Jews were considered enemies too. Only spouses in so-called mixed marriages with “Aryans” were initially protected from deportation. However, both spouses in such a marriage were degraded as persons, restricted in their employment possibilities, and found their lives controlled by all kinds of regulations.

National Socialist propaganda defamed people by spreading negative stereotypes about them and fomenting social hatred against them. Ultimately, the plan provided for the persecution and extermination of entire population groups. This was carried out with the tools of a modern bureaucratic machine, with targeted arrests, mass deportations and imprisonment in ghettos, with forced-labour and concentration camps, and ultimately with murder in extermination camps.

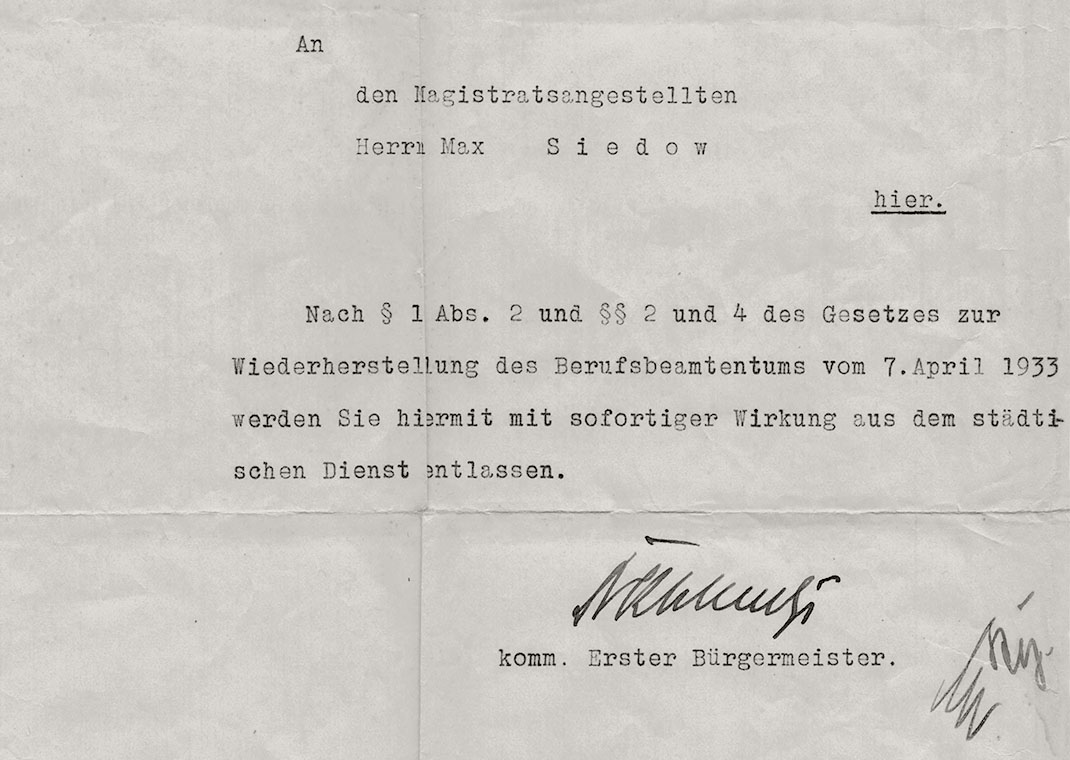

The situation of Jews in Germany changed gradually following the National Socialists’ seizure of power in 1933. From that point on, Jews who had previously been able to lead their own lives found themselves increasingly subjected to state control. Antisemitic ordinances and regulations culminating in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 limited the rights of Jewish citizens to education, family formation, housing and employment, while propaganda encouraging boycotts of Jewish businesses fomented hatred and reached a provisional climax in the pogroms around 9 November 1938.

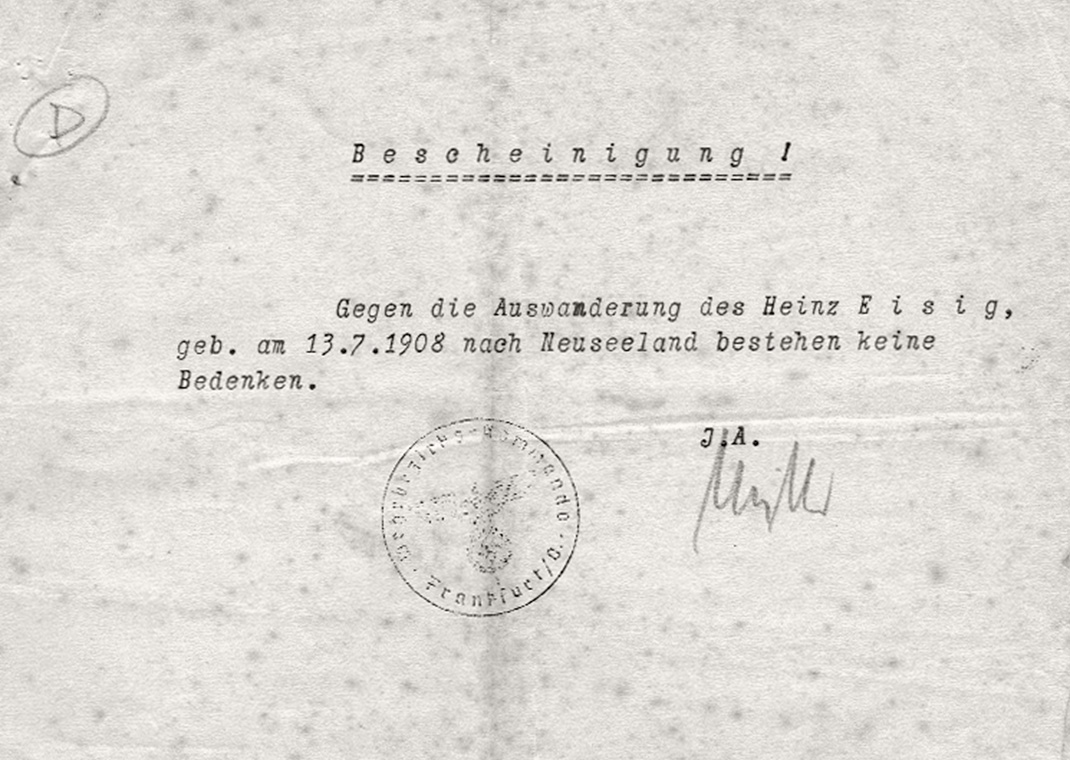

The fates of the Jewish citizens of Fürstenwalde accurately mirror the situation in the “Third Reich” as a whole. Some families decided to leave Germany after 1933. Only few managed to sell their properties in time to avoid “Aryanisation” and expropriation. The destinations to which they fled included supposedly safe European countries as well as New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Brazil – as well as Shanghai, the only place that could be reached without a visa.

Those who stayed behind were initially deprived of their livelihoods by the occupational bans and the November pogroms of 1938. In the same year, Jews were ordered to move out of the houses and flats they had chosen for themselves and forced to move into so-called “Jews’ houses” – known today as “ghetto houses”. These were houses that had previously been owned by Jews – and only Jewish tenants were now allowed to live in them. The express goal of ghettoisation was the systematic concentration and isolation of Jews. From 1942, their houses had to be marked with a Star of David. In Fürstenwalde, for example, the house of the Groß family at Frankfurter Straße 18 and the house of the Kiwi family at Wriezener Straße 12 were designated as “ghetto houses”.

The systematic deportation of Jews to the East began in October 1941. The imminent danger drove many people to commit suicide. The Wannsee Conference in 1942 set the final seal on the Holocaust and the systematic extermination of more than six million people.

Resistance to the National Socialist regime as a reason for persecution

Following its seizure of power in 1933, the National Socialist government strove to suppress and eliminate political opponents, critics of the system and dissidents. Through targeted propaganda and waves of arrests, the Reich government steadily weakened the political opposition. Members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) were subjected to repressive measures; they were persecuted, taken into “protective custody”, or murdered, as were for instance the Fürstenwalde citizens Albert Genz and Richard Soland, who are commemorated today with Stolpersteine.

A turning point for the Social Democratic resistance was the dissolution of the Free Trade Unions on 2 May 1933, the arrest of leading functionaries and the subsequent incorporation of the organisations into the German Labour Front. The ban on the SPD that followed on 22 June 1933 marked the end of the democratic legal system in Germany.

At the time the terror began, people of different social and political backgrounds put up passive or active resistance to the Nazi regime. As everyday heroes, they took in people persecuted on racial or political grounds and offered them shelter. Others, like Richard Weißensteiner from Fürstenwalde, who was a member of the “Red Orchestra” network of resistance groups, opposed the regime by participating in specific actions and voicing public criticism. They were all putting their lives on the line.

Persecution of people with disabilities and mental illnesses

National Socialist ideology devalued people with disabilities or specific illnesses as inferior or unworthy of life. The goal was to make the German people not only “racially pure” but also free of genetically inherited diseases. In 1933, shortly after the seizure of power, the National Socialist government passed the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring”, which provided for the forced sterilisation of the so-called “hereditarily defective”. This was followed by several murder campaigns – under the euphemistic term “euthanasia” (Greek for “the good death”) – that targeted infants, children and adults.

During the war years 1940 and 1941, the National Socialists had a centrally organised campaign to murder people with mental illnesses and disabilities. The name of the campaign, “Aktion T4”, was derived in the post-war period from the address of the office headquarters at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin-Mitte, which today would be next to the site of the Berliner Philharmonie, the home of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. From there, the campaign and its six killing centres were coordinated with the aim of “exterminating life unworthy of life”. On 24 August 1941, the campaign was officially ended, but in practice it continued on a decentralised basis. Employees of the judiciary, the police and the administration – not to mention nurses and doctors – were involved in the murder of a total of 200,000 people.

Text: Justyna Gralak

Translation: Jennifer Feldman